12. Triad Inversions

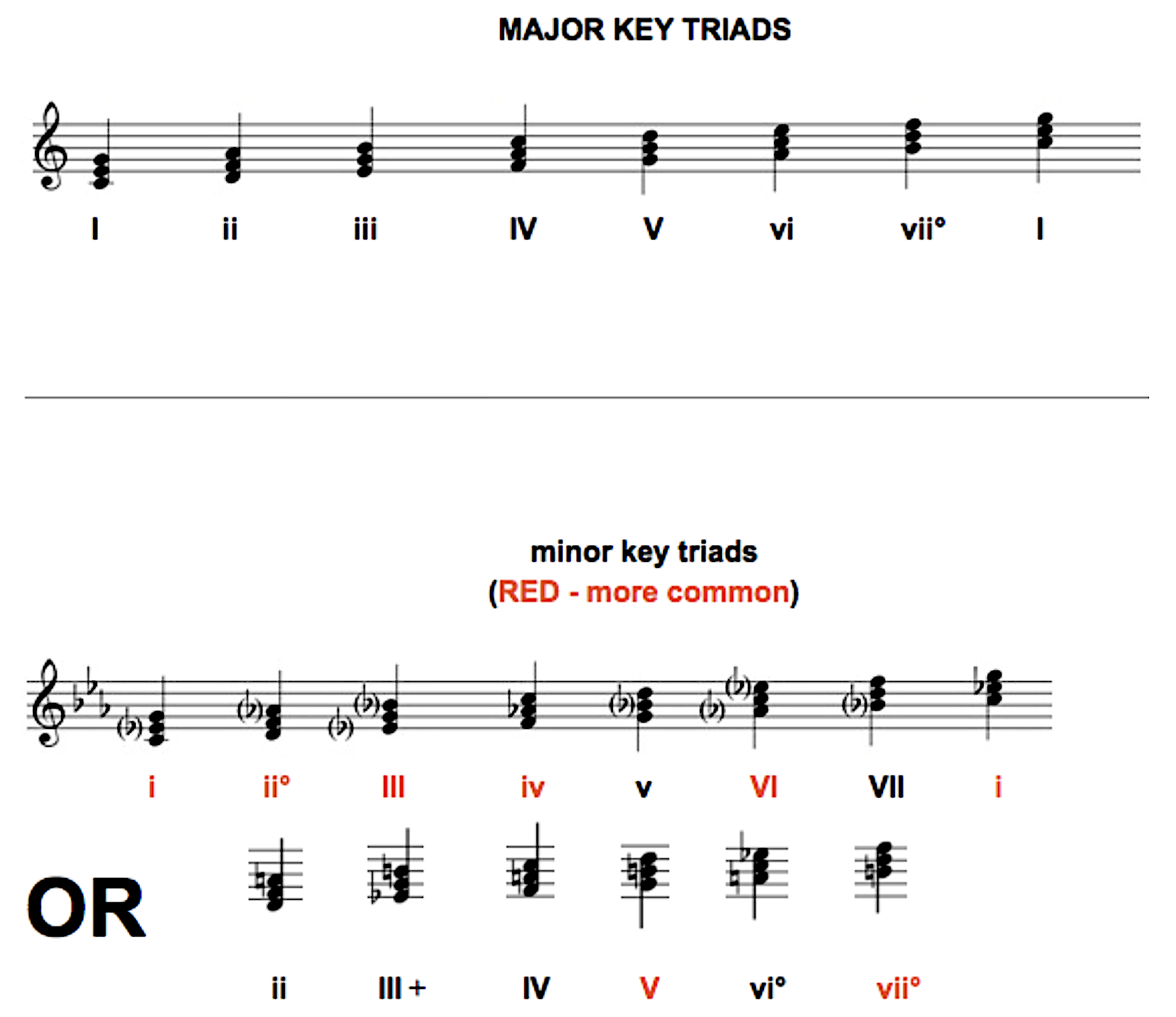

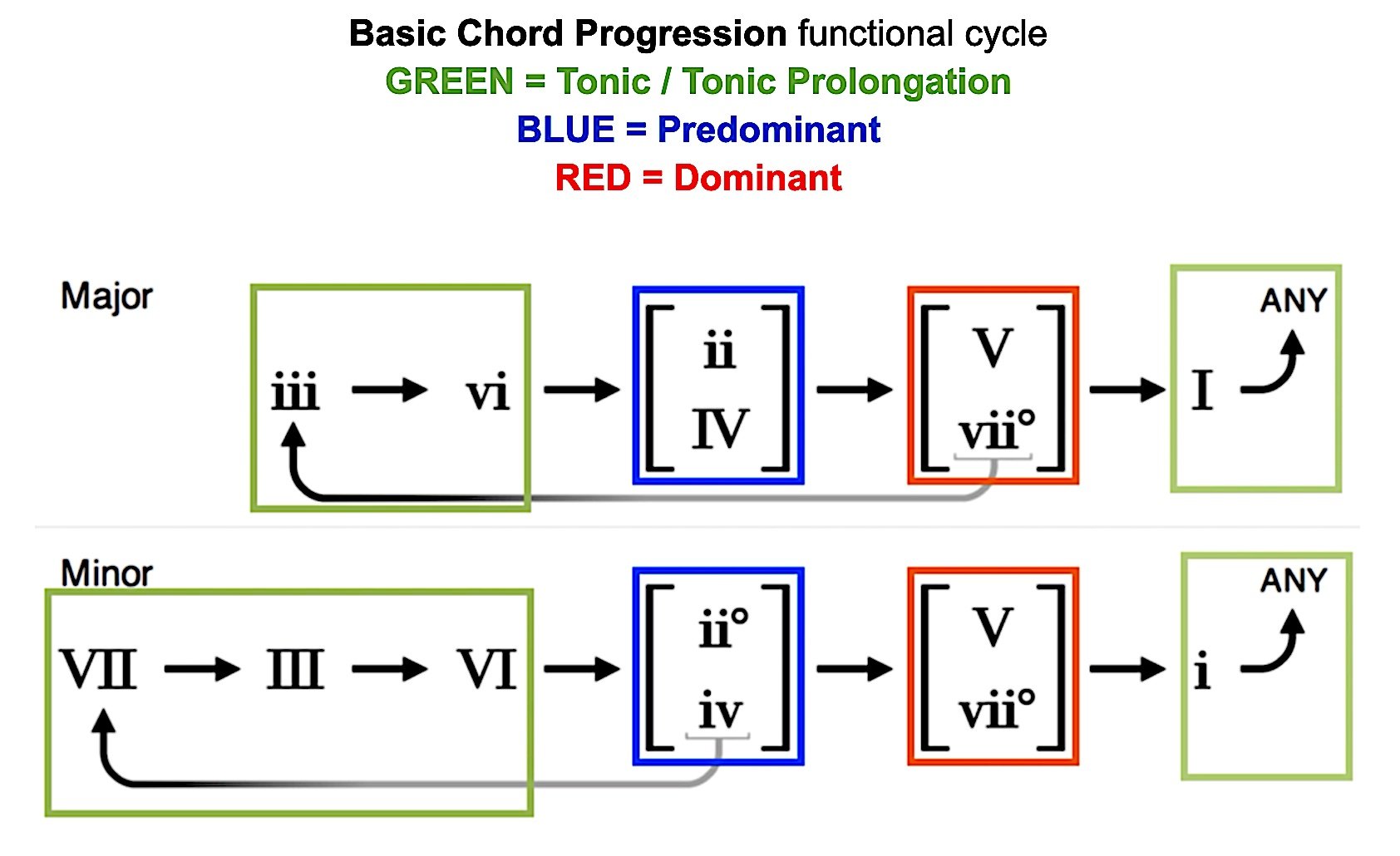

Simple harmony consists of three pitches stacked in thirds. The three pitches heard together as a unit function as triads. Triads can be placed on each of the scale degrees of the major and minor scales. Triads that remain within the key signature, known as basic or diatonic triads, are the basis for harmonic progressions that cycle through the three harmonic functions: Tonic - Predominant - Dominant, before returning to Tonic.

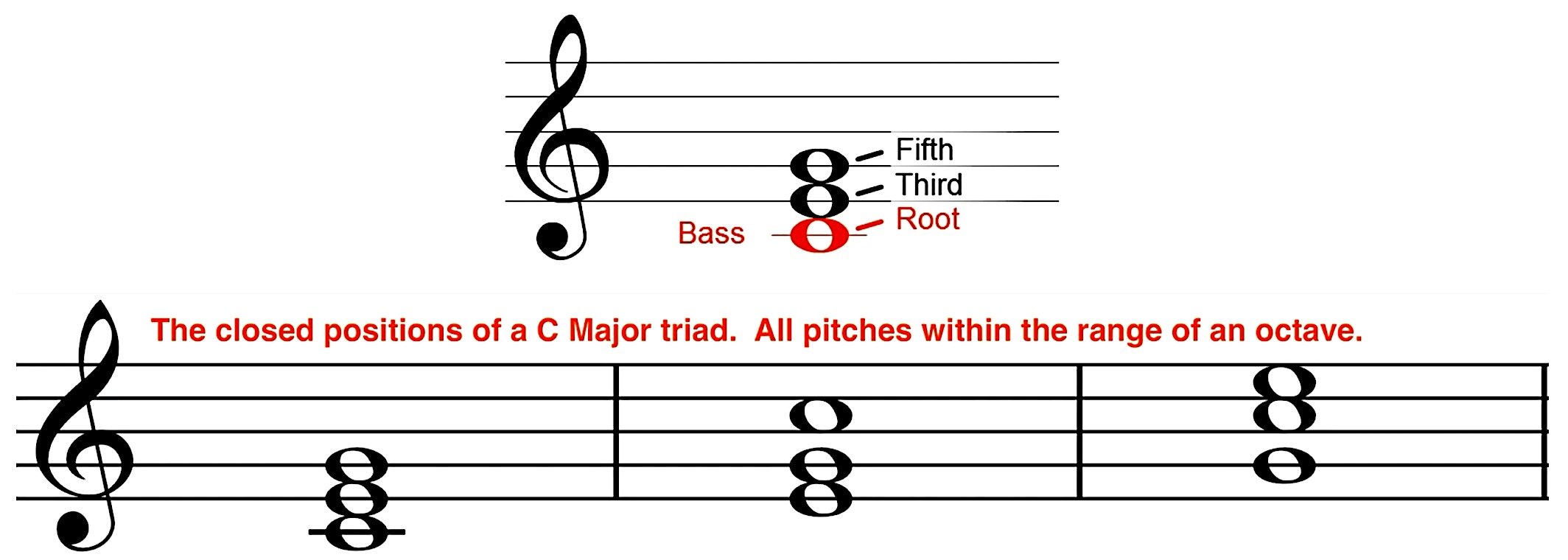

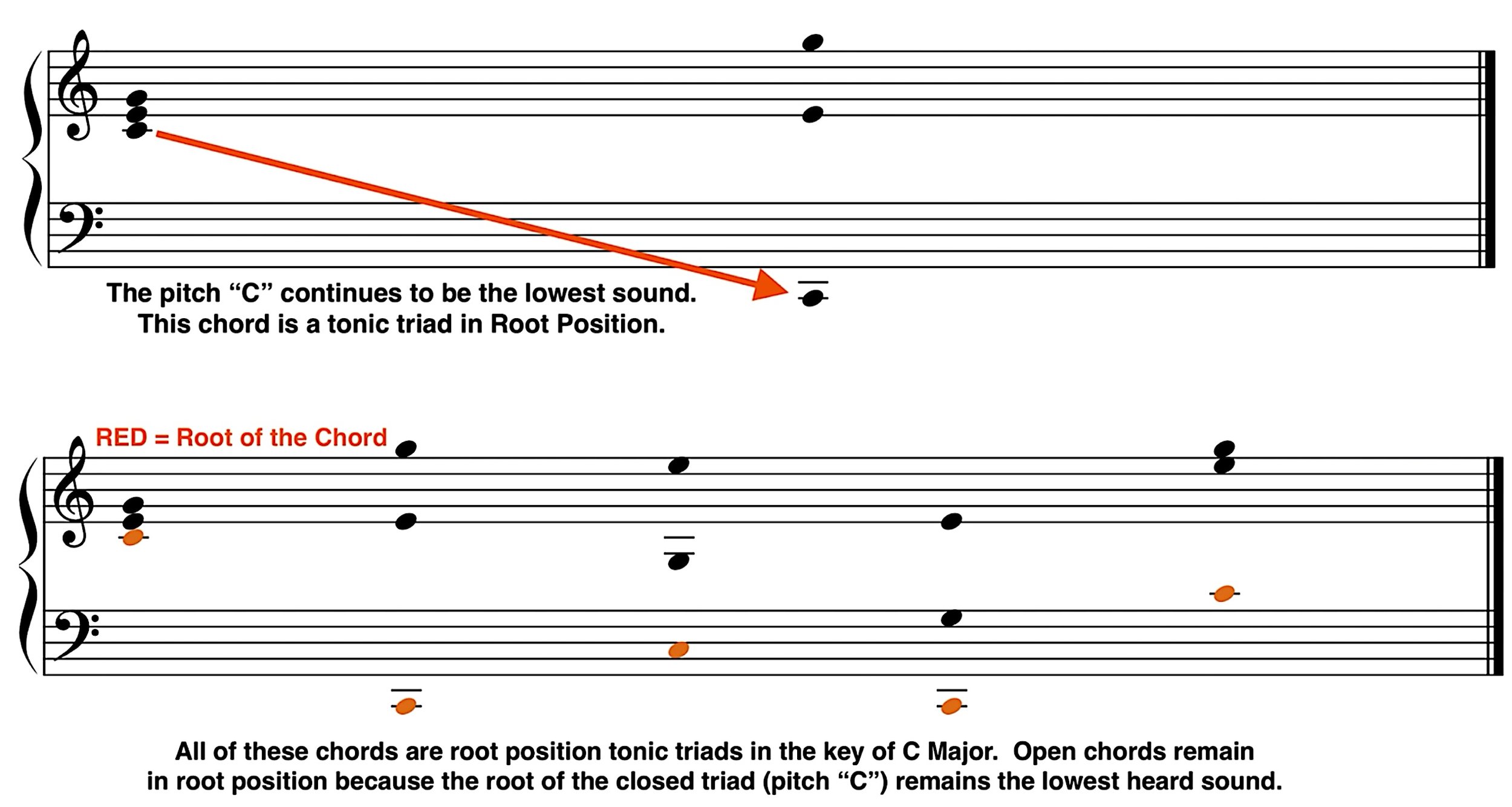

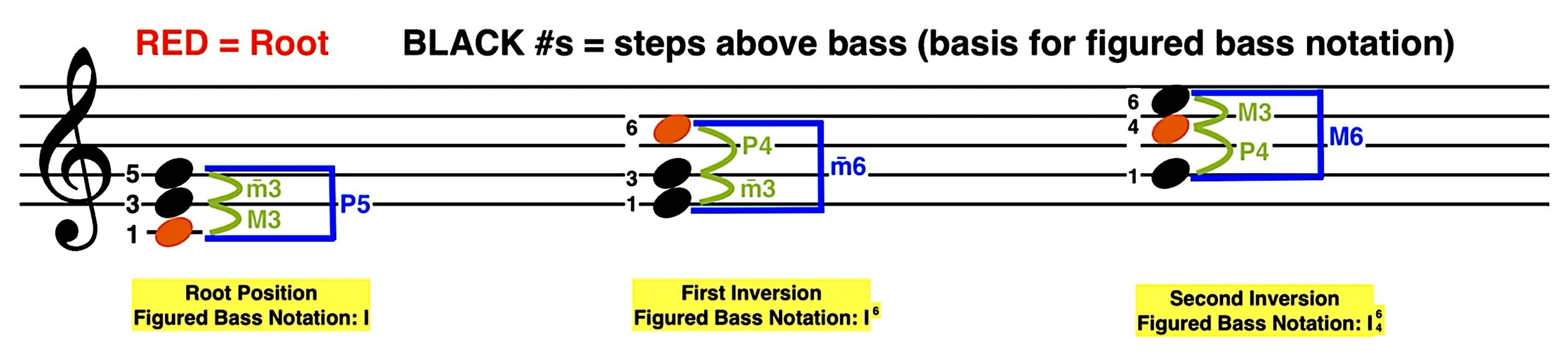

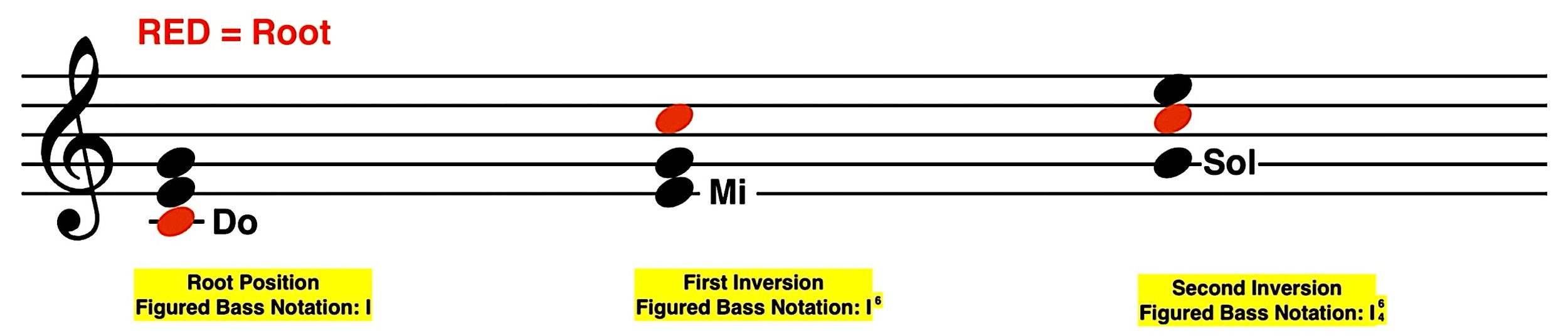

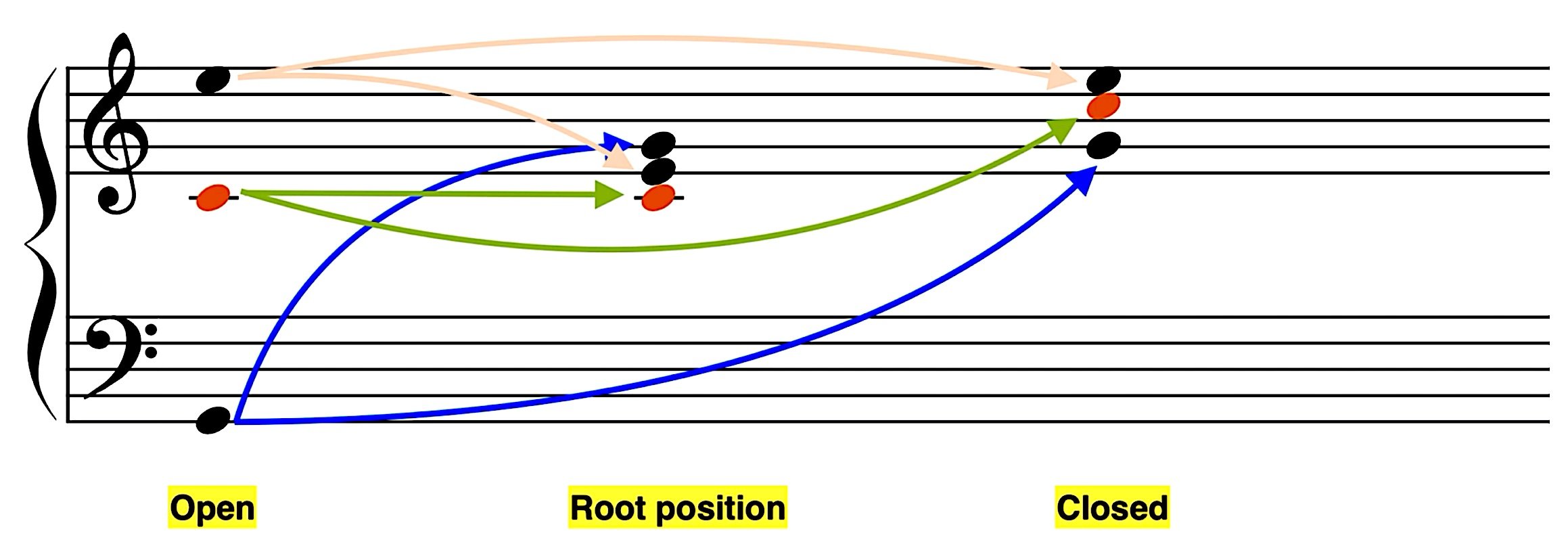

The triads seen above are notated in closed and in root position. A root position chord places the lowest of the three stacked pitches (when stacked in thirds) always as the sounding bass of the chord. A chord is considered to be closed when all of the unique pitches are squashed down to fit within the range of one octave.

A chord is considered to be open when the pitches of a chord are stretched out over multiple octaves. A closed position chord that is stretched out to open position and still retains the same pitch as the sounding bass (the lowest note heard) retains the name of the chord and the harmonic function of the original closed position chord. The “sound” of the chord is different but the function is exactly the same. The important pitch to focus on is the bass note and, as long as this pitch remains on the bottom of the sound, every other note above this bass can be reordered, spaced out, or scrunched up while still retaining the same harmonic function.

However, once the lowest sounding note of the chord is shifted to a different pitch, the chord’s inversion has then been changed. In its most basic definition, an inversion is simply taking anything and flipping it upside down or inside out.

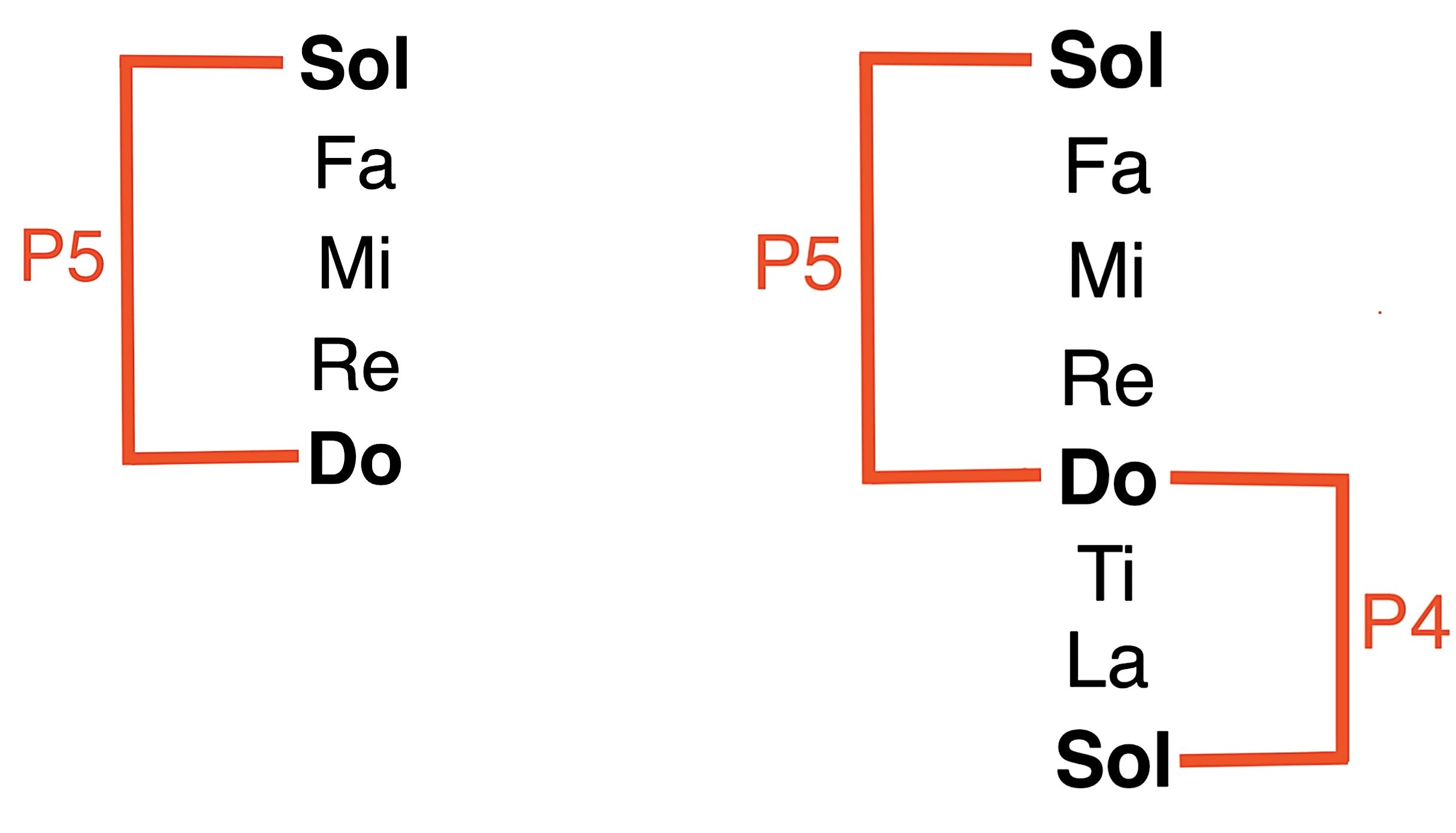

Inversions in music begin with intervals. For example, an interval of a perfect 5th, represented in this case as the solfege syllable “Do” moving up to “Sol”, transforms into a perfect 4th when inverted. The relationship between the two pitches has been inverted, and the result is a new sonority/quality.

Inversions of triads and chords where there are more than two unique notes present works in a similar fashion to the inversion of intervals. Since there are more than two notes, there are also more possibilities for inversion positions. A good analogy for how inversions of chords work is the bicycle team trial strategy used by road bike athletes during competitions.

How Chord Inversions Work using a bicycle team trial analogy - Bass vs Root

When we take triads in closed position (scrunched up to within one octave), placing a different solfege syllable on the bass (the lowest sound we can hear), changes the makeup of the intervals that are creating a triad. The note names themselves don’t change but the distance between each note or the intervals does change.

An additional and more fruitful method to identifying triad inversions is to focus on identifying the solfege syllable present at the bottom of the sounding chord, regardless of which intervals are being created in the upper voices.

The neat stacking of thirds and fourths present in triads in root position and their inversions is clearly visible only when the triad is configured in a closed chord position. The act of reconfiguring the sounding chord into its root position version, and then transplanting the pitches into the chord’s closed position is a key skill for musicians to acquire. The development of this skill allows musicians to analyze the bass note in relation to the chord’s function and inversion.

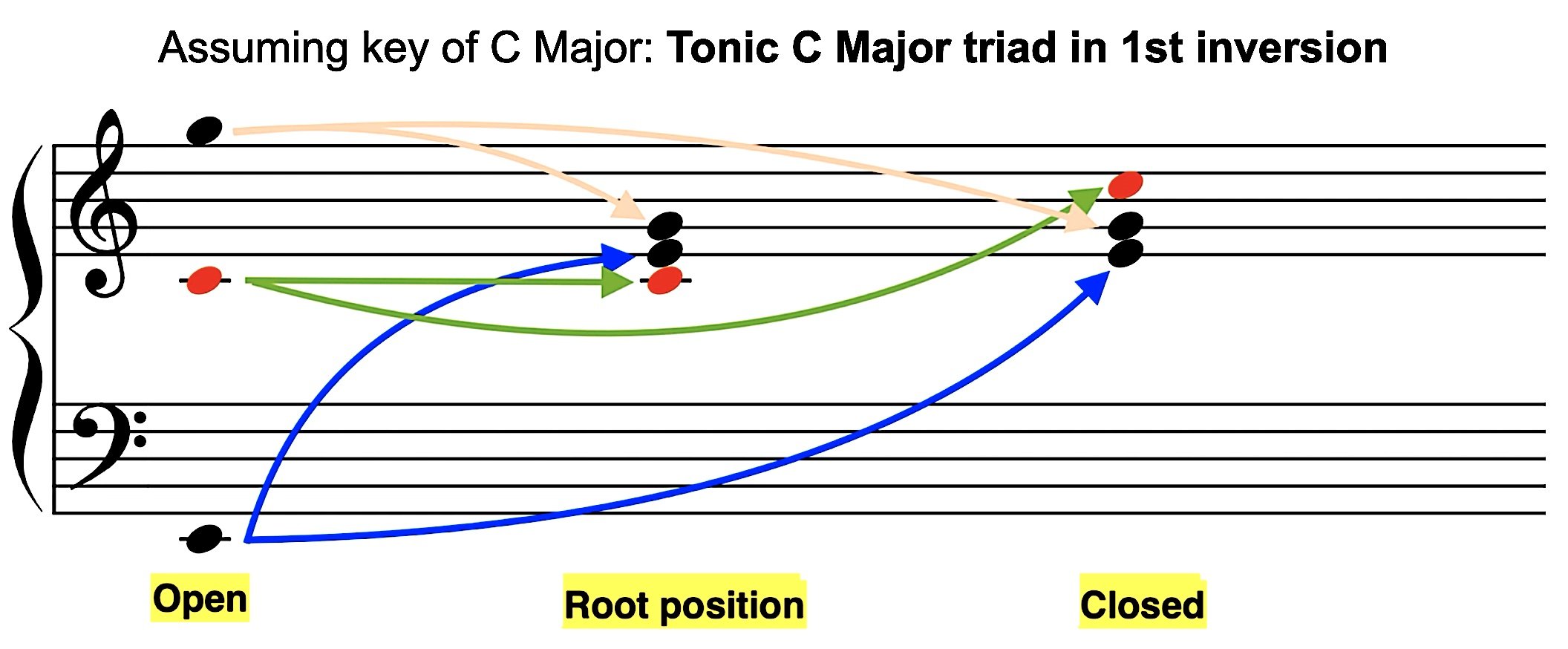

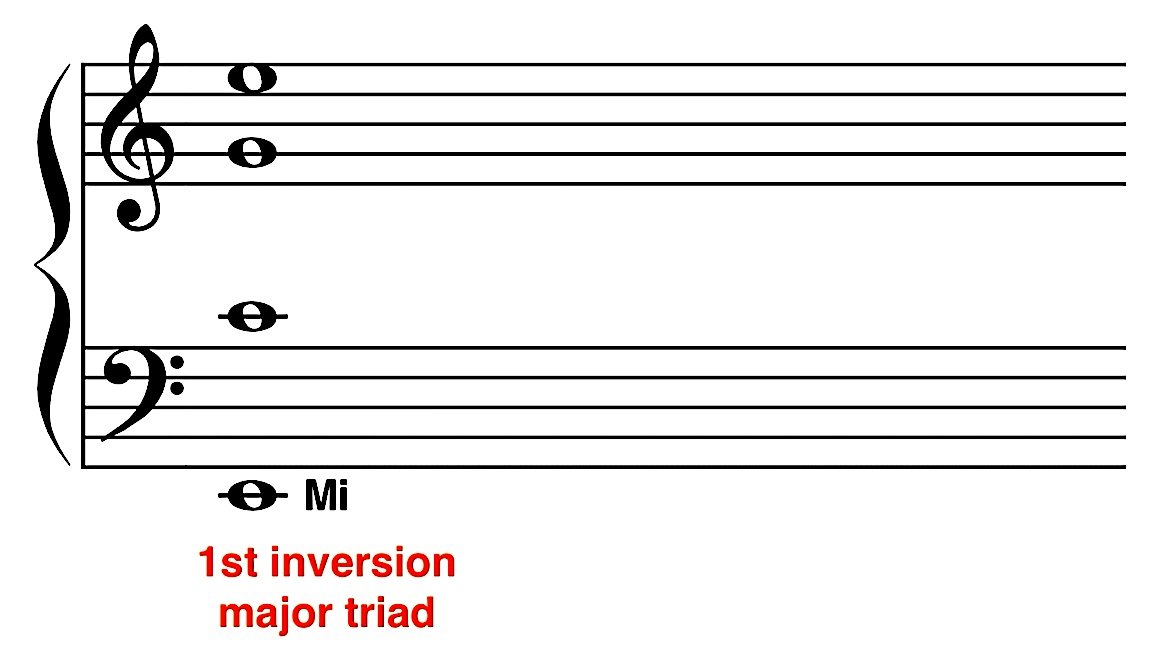

In the example seen below, a C Major triad is seen in an open position. Although the notes are spaced very far apart, the pitches still constitute a C Major triad (pitches C, E, G.) If we consider the key to also be C Major, the function of this chord is Tonic regardless of the open position. With the bass on the pitch E, which is the 3rd of the triad when it is in root position, the tonic C Major triad is considered to be in 1st inversion.

Similarly, the inversion changes when a different part of the chord is featured as the lowest sounding pitch. The example below illustrates an open C Major tonic triad in 2nd inversion, with the 5th of the root position triad as the bass.

Why does harmony bother with inversions? Couldn’t harmony simply be in root position all the time to make matters more streamlined? There are two big reasons why inversions are present in harmony.

The most obvious answer is that each one of a triad’s inversions will have a different sound. To illustrate, a root position tonic triad, especially one that doubles its root in an additional voice, is the strongest version of the tonic function. In contrast, a tonic triad in 2nd inversion, where the fifth scale degree (“Sol”) is the bass of the chord, is the weakest version of the tonic function. The 2nd inversion tonic triad is so functionally weak that listeners will hear these chords and register them as having a dominant function. The bass of these chords rests squarely on the 5th scale degree of the key and deceives the listener to feel a dominant function despite the pitches themselves outlining a tonic triad. resting on the syllable Sol even though the notes themselves are making up a tonic triad.

The second reason is more practical in nature. Having the flexibility to display chords in different inversions allows music to have more linear and vertical variety, and also allows musical lines to have more flow. Take, for example, the 3rd movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 1, as seen below. The voices of the arpeggios played on the left hand never move by more than one step. If these chords had been written in root position, that same passage would necessitate the pianist’s hand to lift and jump around the keyboard. However, through the use of inversions, the harmonic progression instills musical flow and is more technically reasonable for the performer.

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 1 Op. 2 - IV. Prestissimo

Philip Glass, one of the founders of modern minimalism music, uses triad inversions in much the same way as Beethoven and for the same purposes: to add variety and create technical and musical flow. In the passage seen below, taken from “Piano Etude No. 17”. Philip Glass repeats the same four measure harmonic progression throughout the duration of the 8 minute work. The repeating harmony could sound mundane if it is simply the same thing over and over again. However, Philip Glass changes the inversions of the chords (among other things) each time the harmonic cycle is repeated. The use of inversions, as is also the case in the Beethoven example, gives the music an ascending direction and growing intensity thanks to the bass line that progressively creeps up in pitch one step at a time.

Excerpt from PHILIP GLASS Etude No. 17

A useful and methodical approach to aurally recognize inversions in music can be broken down to three specific steps:

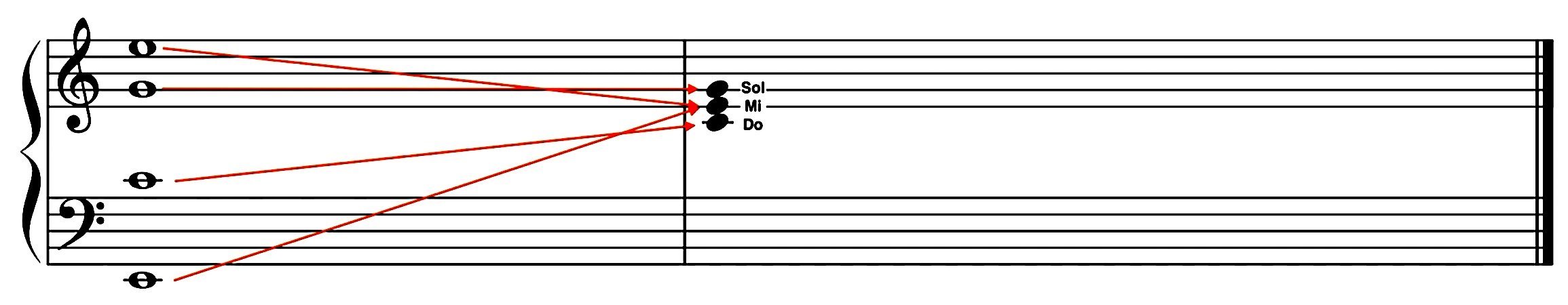

STEP 1: “Hear it in root and closed position”: The first step is to listen and absorb the overall sound of the sounding triad and to reorganize it into its root and closed position version.

Hear it in root and closed position

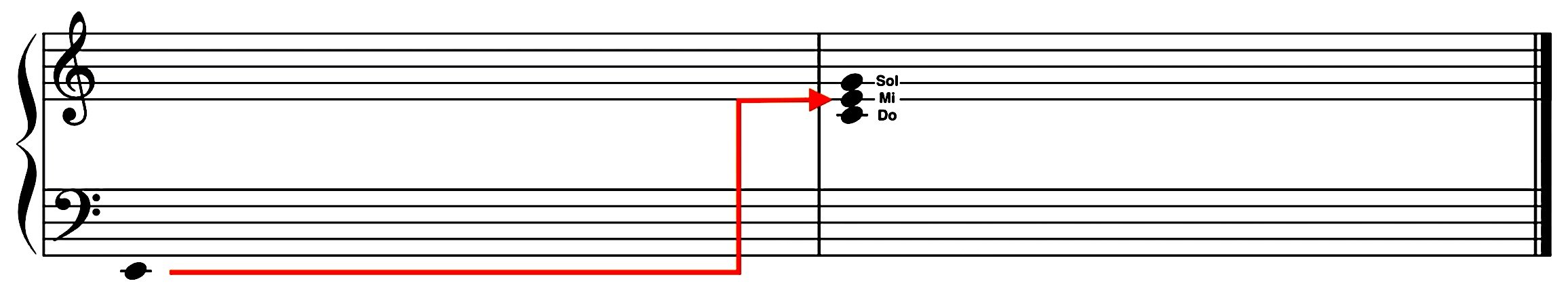

STEP 2: “Hear the bass”: The next step is to use the mind’s ability to spotlight specific sounds while filtering others out (this is known in psychology as the “cocktail party effect”) to hone in on the lowest pitched note of the original chord.

Hear the Bass

STEP 3: “Fit the bass into the triad”: The third step is to go back to the closed root position chord from Step 1 and match the bass pitch from Step 2 to one of the three pitches from the triad.

Fit the bass into the triad

Depending on what part of the root position chord the bass from the original chord fits into, the inversion of the triad can be identified. The C Major open position chord seen above is now identified as a C Major triad in 1st inversion.

Hearing chords and reconfiguring them into their root position versions is an important step to understanding functional harmony, and adds another tool to help appreciate different types of music heard throughout history and throughout the world.